The Long Game

by Susan Hinckley

Little Nancy Etticoat

In a white petticoat,

And a red nose;

The longer she stands

The shorter she grows.

My grandma died when I was 8,

and when they cleaned out her house I inherited a very old book of Mother Goose rhymes that my mother and her sisters had grown up with. It had wonderful illustrations for many verses, but there was no illustration of Little Nancy, who was a riddle as well as a rhyme. I hadn’t the faintest idea what it was talking about. Maybe I wasn’t that smart, but in my defense, candles were a familiar household staple when the nursery rhyme came to be, but mostly absent from my 1970s world. We didn’t use them at home or church.

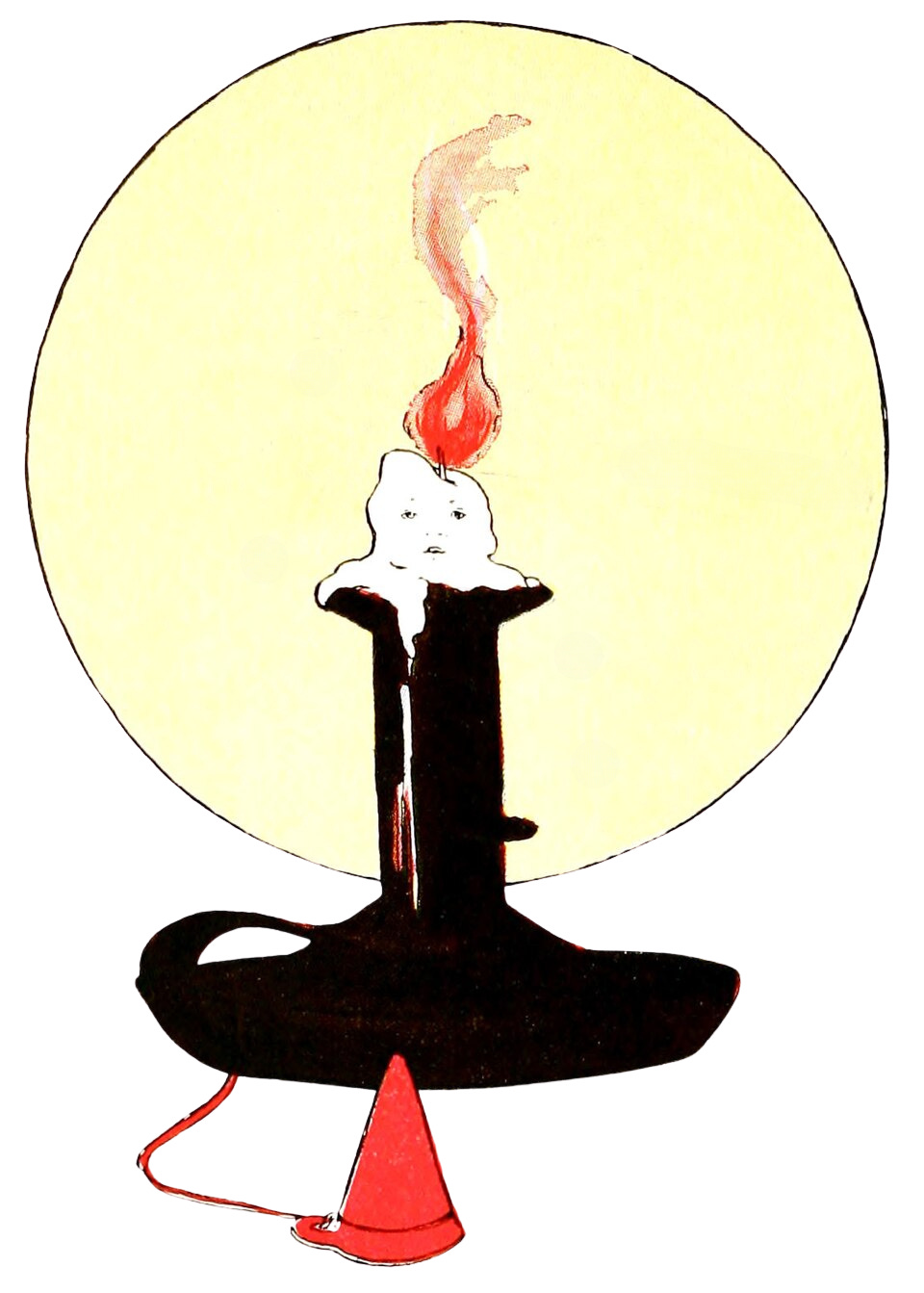

I forgot this verse until I bought my first child her own Mother Goose book. It had this classic illustration, and I had a big moment of Duh.

As I heard Jim Finley describe it recently, “We’re all melting like candles.”

Yes we are, and at this phase of my life, I don’t know much but I’m beginning to know how Nancy felt—I’ve been standing quite a long time. I’ve never been tall, but now when I look in the mirror, my older face tells a hard truth: I’m short.

Most of the time I successfully ignore the facts, but as the years twirl by it’s getting harder. I’ve reached a stage where the body and the story can’t quite hold themselves together.

This may be why Presence has begun to beat an insistent drum. In the past decade, someone or something has been trying to get my attention, to convince me that no matter how hard I run, I can’t run away from what’s real, so I may as well stop trying. I’d approached life persuaded that there was always something better around the next corner, and my religion didn’t help; from church, the main idea I picked up was that the point of this life was actually to focus on the next.

The shorter I grow, the more I understand that The Here and Now has been the gift all along—a gift I’ve been trying to exchange for as long as I can remember.

A dear friend used to quip, “The older we get, the more like ourselves we become.” I was in my 20s when she started saying that, and it always made me laugh but inside I was thinking, “Oh no! Please tell me there’s a Me coming that’s better than this.” I didn’t know how to love or value myself—either it wasn’t in the nature, or it wasn’t in the nurture, and after a point it didn’t really matter which.

A big part of growing older has been coming to accept my humanness. It’s a lesson my body is getting obvious with—if younger me had been paying any real attention, I’d have noticed a suspicious amount of old people. That should have been a clue that there’s a human path, we’re all on it, and I would not turn out to be the lone exception.

But for most of my life, in my heart I believed my humanity was not the important part of it. “Human” might do for other people; I had a perfection mandate, a thing just out of reach that I assumed I must chase until I die.

Onward and upward, always always always. Anywhere but here.

I thought getting perfect was hard, but it turns out getting human is the real work.

Presence, letting myself BE right here in the right now—noticing it, allowing it, breathing it, steeping in it, letting it be what it is without needing to find any shiny parts to make it (or myself) more lovable, staying open to what it has to teach me—has come with some truly gut-wrenching lessons. I thought getting perfect was hard, but it turns out getting human is the real work.

Or as Carmen Acevedo Butcher says, “Being human is harder than being spiritual.”

Do Mormons want to do this particular hard work though? We’re a worker-bee church, anxiously engaged in doing all the things all the time, right? And it hasn’t ever felt easy to me, like I could just coast. I never felt like I was avoiding all the dirty work like growing or grubbing around with the messy people, getting covered in stains. But as I think about it, I must admit that might have been my goal with everything I was doing—scriptures, meetings, lessons, temple work, and keeping my kids in a straight line behind me—do this work to avoid having to do that. Of course perfection could never be here or now, and its hamster wheel only distracted me because I was running.

Getting knocked off the wheel felt confusing at first—I kept trying to climb back on because I thought it was the only way to get where I wanted to go. But about the same time I noticed myself thrown off the wheel and lying face down in life’s dirt, I noticed for the first time that the Jesus in the Bible had more to do with the mess of being a person than with the perfection of not being one. I realized that all the spirituality in the world wouldn’t teach me how to be like Jesus because doing the Jesus-work required me to get hands on with my own—and everyone else’s—humanity.

“God is about presence,” a Christian friend (with whom I sometimes disagree theologically) recently announced to me via Marco Polo on his morning commute. “When I was small, I thought God was about rules. And then, for most of my life, I thought about God as Law Giver and Provider … somewhere out there. Now I realize God is about presence, right now, whether you’re ready or not, and it’s probably best not to try to be ‘ready,’ for a bunch of reasons. Which is interesting, because if God is about presence, that actually comes back to how I thought about God when I was really little, up to about age 7. Then I didn’t question it, I just liked it. It’s so cool being human—you start to realize what human means, and it’s cosmic.”

I paused to look up cosmic: Limitless. Universal.

Yes.

He continued, “The real problem, ontologically, is that I’d rather go to McDonald’s, but I like to look in on the folks behind the counter at Wendy’s—they’re my pals. A few of them are going through really hard stuff. And already, from clear up the street here, I can see there may be a person sitting on the Wendy’s corner who needs to be fed.”

Spirituality + Jesus—humanness as somehow both cosmic and at Wendy’s—was the perfect New Year’s message. His ramble arrived as a small tap on the shoulder from the Universe, pulling my attention back to that place I mean to stay but can’t seem to stop wandering away from: Presence. When you meditate and you get distracted by thoughts, you redirect, bringing yourself back again and again to your practice—my life is one long distraction. I redirect.

Christianity has not rewarded a fully-embodied spirituality though. If a 7 year old can recognize God as presence—if we can know the Source in our bones—why do we need the church?

This means at least on some level, churches are probably invested in keeping us separated from the truth of our own bones and hearts and humanity. I get it—a middleman will naturally defend his position.

For me, reimagining my faith began with the full acceptance of my human experience. Jesus was, after all, a human—in addition to whatever else he is. For now, this life is the point at which his experience and mine intersect. But it’s not for his humanness that we are taught to worship him, it is for having transcended it.

No wonder I learned to show up at church with only the shiniest parts of myself showing. No wonder I was taught that the natural man was an enemy to God (and if the man was, I could only wonder how that god might feel about the even-more-earthy woman?) No wonder I internalized that progress must include casting aside my most human parts: my failings, wants, hungers, needs, and desires—the common thread by which I’m connected to all my human siblings.

All of which runs completely counter to Presence.

How could I love the thing I had not been taught to reverence? And why would I believe God loves me if I had not been taught to love myself?

Returning church members to ourselves—and to our lives—is the missionary work I want to do now.

I’ve been reading a book called Give Me a Word: The Promise of an Ancient Practice to Guide Your Year, by Christine Valters Paintner. She describes how people would come to the desert fathers and mothers—"elders who, in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, went to the deserts of Egypt, Syria, and Palestine to cultivate a life of radical simplicity and ongoing devotion to the presence of the divine in their lives”—and say, “Give me a word.”

“This tradition of asking for a word was a way of seeking something on which to ponder for many days, weeks, months, sometimes a whole lifetime. A ‘word’ was often a short phrase to nourish and challenge the receiver. A word was meant to be wrestled with and slowly grown into.”

The point the book makes is, you’re not supposed to choose your own word—the word is supposed to choose you. I’m not the kind of person who picks a word every year, but sometimes ideas have presented themselves to me that have felt important. And this kind of thing—right up at the edge of woo-woo—has kinda been my shtick for a long time. One thing any kid growing up in my house could count on is that at some point during the day, I was going to read her horoscope from the newspaper on the kitchen counter. If her friends came over, they were going to have to endure hearing theirs, too.

So while I’ve been wandering around waiting for a word to choose me the past few weeks (and I’m not yet sure it has, or will), I’ve been paying extra attention to random stuff. One of my own horoscopes this week said this:

“You’re playing a long game.”

As I picked up those words they settled into a familiar groove, like they’d only just now fallen out of my head after living there forever.

“It is said that all you are seeking is also seeking you. That is, if you lie still, sit still, it will find you. It has been waiting for you for a long time. Once it is here, don’t move away. Rest. See what happens next.”

—Clarissa Pinkola Estes

Whether or not this phrase has chosen me remains to be seen, but it means something to me right now and I will continue to sit with it and see what happens next.

Though it exists in moments, presence is actually the long game, the thing that never ends. Paradoxically, my human life and this body with which I have grown so familiar are not permanent. I’m a very short woman to be trying to learn to play such a game—at 62 my white petticoat has grown longer than what’s left of me. But the tension between these two ideas—never ending presence within a life that will—has just the right feel. I take hold of them together; I will try not to move away.

Richard Rohr writes, “There must be, and, if we are honest, there always will be at least one situation in our lives that we cannot fix, control, explain, change, or even understand.”

Just one? Sometimes that feels like a description of life, and some patches can be pretty rough. But isn’t this place he’s describing—where we encounter what’s real, then choose to sit there with it—the place we find the potential for growth? Doesn’t what feels like we might not survive it also bring us one step closer to our true selves, and therefore to God?

Richard Rohr reminds me, “I can live and work with all of it, because apparently God can. Everything belongs.”

Come to think of it, “everything belongs” is a phrase that chose me several years ago. Those words came into my life and changed the way I thought about so much—about church and Jesus and faith and every spiritual thing I was struggling with at the time, but more importantly about myself. Somehow that phrase “showed me to my seat” in my own life, introducing me to the practice of sitting with my humanness, allowing myself to just be—and be enough—in every moment and circumstance.

Author Maeve Binchy said, “I’m getting better, happier, and nicer as I grow older, so I would be terrific in a couple of hundred years’ time.”

Me too, and I’m not talking about some kind of eternal progression toward my own perfection. I mean I love myself and my life right now in ways I never knew how to before.

Thank goodness it’s a long game—I’m only now beginning to practice it.

Susan Hinckley

Thanks for supporting Say More and ALSSI. Have something to say? Join the conversation: Send us a voicemail, start a chat thread, or write a piece for a future issue!

Loved this read. It gave me just the right start to 2026. Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Susan. They were exactly what I needed to begin to channel the kind of mindset of presence and ease that I am hoping will guide this coming year (and hopefully beyond!).

Thank you for letting me be part of your game. I learned so much from you and from the people you share on your podcast and writings. When I saw my subscription receipt today, it reminded me of how much this means to me.